Four of this year’s five documentary shorts nominated for the Academy Award open Friday (Feb. 17) a the Tivoli Theatre.

And a more powerful handful of short films you’d have a hard time finding.

(The fifth nominated film, “God is Bigger Than Elvis,” about Elvis Presley co-star Dolores Hart and her decision to become a Benedictine nun, is not being made available for commercial presentation as part of the Oscar shorts package.)

Some of these titles are hard to watch. All are important.

“THE BARBER OF BIRMINGHAM: FOOT SOLDIER OF THE CIVIL RIGHTS MOVEMENT” My rating: B+

18 minutes

Robin Fryday and Gail Dolgin’s film centers on 85-year-old James Armstrong, a barber in Birmingham, Alabama, who marched for civil rights with Martin Luther King Jr. and now watches the election of America’s first black president.

He’s a lovely old fellow. His barber shop’s walls are covered with old news clippings about the Civil Rights movement and a sign advises patrons: “If you don’t vote, don’t talk politics in here.”

Armstrong is a churchgoer who says with pride that “I’ve been in jail six times…in this city.” He drives a car literally held together with duct tape.

“Barber of Birgmingham” cuts between archival footage from the ‘60s, interviews with veteran marchers (now in their 80s), and shots of political activity as the 2008 presidential election heats up.

The film isn’t particularly well organized — Fryday and Dolgin seem content to throw stuff against the wall and see what sticks — but still it contains moments of breathtaking power.

“INCIDENT IN NEW BAGHDAD” My rating: B

22 minutes

James Spione’s doc focuses on Ethan McCord, a Wichita, Kansas, a single dad and veteran of the Iraq conflict who has endured post traumatic stress syndrome.

His trauma stems from a controversial and much-publicized July 2007 incident in which U.S. Apache helicopters fired on suspected terrorists, killing a father and severely wounding two children. McCord carried one of the young victims to the medics.

Spione has been profoundly changed by his experiences. He now claims that that American intervention in Iraq was a waste of time: ”The only thing I was doing there was trying to survive and make it home.”

Spione’s film is sad, angry, and for many it will be uncomfortably political.

“THE TSUNAMI AND THE CHERRY BLOSSOM” My rating: A-

“THE TSUNAMI AND THE CHERRY BLOSSOM” My rating: A-

40 minutes

This devastating film opens with familiar (but no less ghastly for that) footage of the 2011 Japanese tsunami engulfing a seaside town. It’s presented unedited, just as it was shot by a horrified resident looking down on his home from a high hill.

It then turns to the survivors. Many are in despair.

“I lost the meaning of life. I have nothing. That’s it.”

“I felt like crying but I don’t have time for that.”

There is footage of the wreckage. Of the rescue (actually corpse recovery) efforts.

But then filmmakers Lucy Walker and Kira Carstensen do something quite wonderful. They turn away from the devastation and begin examining the importance of the cherry blossom in Japanese culture. Just a month after the tsunami, a cherry tree bloomed amidst the devastation.

The cherry blossom, or sakura, traditionally is a sign of spring and rebirth for the Japanese.

“The cherry is the tree that will sympathize with you,” says a botanist without the slightest trace of irony. He absolutely believes it.

And so “The Tsunami and the Cherry Blossom” begins in tragedy and ends in transcendence.

40 minutes

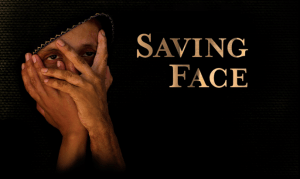

If you’re not reduced to a blubbering mess by the end of Daniel Junge and Sharmeen Obaid-Chinoy’s film, you are probably beyond hope.

Their subjects are Pakistani women who have become victims of disfiguring acid attacks. These women have angered their men folk — some have asked for a divorce, others simply don’t please their husbands — and they’ve had acid thrown in their faces.

Apparently this is a widespread phenomenon in this overwhelmingly paternalistic society.

Our first sight of one of these women is so horrifying it’s like being punched in the chest.

But Junge and Obaid-Chinoy get beyond the hideous scarring to find the hopeful souls underneath. That’s what makes the film bearable.

In addition to the women there’s Dr. Mohammad Jawad, born in Parkistan but now living in London where he runs a successful plastic surgery practice.

“I love to do my breast work,” he says, “but what I’m known for is my bun work.”

That may sound shallow but, God bless him, the jovial Dr. Jawad regularly returns to Pakistan to operate on the victims of acid attacks. He does so without pay.

Another plot thread follows the efforts of a female member of Pakistan’s Parliament to pass legislation that would impose mandatory life sentences on men who engage in these attacks.

The film’s depiction of modern Pakistan is head-spinning, a world of big-screen TVs, glowing neon and modern shopping malls coexisting with a mentality right out of the Dark Ages.

At least “Saving Face” offers some hope that things are changing.

| Robert W. Butler

Leave a comment