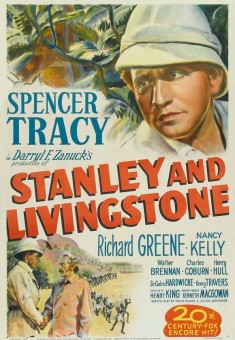

“Stanley and Livingstone” screens at 1:30 p.m. Saturday, May 17, 2014 in the Durwood Film Vault of the Kansas City Central Library, 14W. 10th St. Admission is free. It’s part of the year-long film series Hollywood’s Greatest Year, featuring movies released in 1939.

In 1871 the American newspaper reporter Henry Stanley nearly died searching Africa for the “lost” Scottish missionary David Livingstone. It is one of those real-life adventures seemingly made to order for the movies.

And despite a couple of cheesy “Hollywood” touches, 1939’s “Stanley and Livingstone” is a hugely satisfying adventure yarn.

Spencer Tracy plays Stanley, sent by his publisher, James Gordon Bennett Jr. of The New York Herald, to find out what had happened to Livingstone, missing for four years in Africa’s vast interior.

An investigation by a British newspaper had concluded that Livingstone was dead, but Bennett wasn’t buying it. Besides, Bennett was pathologically anti-British, and he was willing to invest much time, money, and manpower in proving that the English newspaper got it all wrong.

And so Stanley mounted an expedition, enduring searing heat, driving rain, disease, starvation, and attacks by hostile tribes.

Tracy and co-star Walter Brennan (as a folksy Wild West Indian fighter who accompanies Stanley on the trek) never had to leave the comfort of the 20th Century Fox back lot to make the film. And yet the picture is crammed with stupendously authentic scenes set in Africa.

For that you can credit Mrs. Martin Johnson, identified in the film’s credits as the technical director in charge of the safari sequences shot in Kenya, Tanganyika, and Uganda.

Osa Johnson was the widow of Martin Johnson (1884-1937), a native of Chanute, Kansas. In the 1920s and ‘30s the Johnsons became household names for their exotic documentaries filmed in the world’s most far-flung and oft-times dangerous locales. The Johnsons were real-life adventurers whose exploits are celebrated in the Martin and Osa Johnson Safari Museum in Chanute.

Fox honcho Daryl F. Zanuck wisely hired Osa Johnson to take a camera crew to Africa to film the spectacular on-site passages that would be seamlessly edited into the studio-shot footage produced by director Henry King.

Johnson and her director (Otto Brower) staged the safari sequences using body doubles for Tracy and Brennan, whose characters are usually seen from a distance. For closeups, back on the Fox lot the actors were filmed against rear-screen projections of Johnson’s outdoor coverage.

It sounds kind of hokey, but in reality it works very well. In fact, some of Johnson’s footage of the safari members moving through vast herds of African wildlife, climbing mountains, and fording streams is jaw-droppingly beautiful.

A sequence in which Stanley and company are pursued by thousands of hostile native warriors who come pouring over a hill like a human tidal wave is absolutely epic. It wouldn’t be matched for another 25 years, when the British movie “Zulu” depicted the siege of English soldiers at the battle of Rourke’s Drift in 1879 in South Africa.

After a year of unendurable hardships, Stanley did find Livingstone (Sir Cedric Hardwicke) living with a tribe in Tanganyika, leading to the immortal words, “Dr. Livingstone, I presume?”

After a year of unendurable hardships, Stanley did find Livingstone (Sir Cedric Hardwicke) living with a tribe in Tanganyika, leading to the immortal words, “Dr. Livingstone, I presume?”

This could have been the end of the movie. Mission accomplished. But at this point the screenplay by Philip Dunne and Julien Josephson is just starting to get interesting.

That’s because Livingstone, far from being your typical imperialist colonialist, is a truly religious man with a genuine concern not only for his parishoners’ souls, but for their overall well being.

In a telling scene, Stanley finds one of Livingstone’s congregants going through his belongings and, with the righteous fury of a wronged white man, begins beating the miscreant. Livingstone intervenes, pointing out that the thief has gone for several weeks without backsliding, and that he deserves some credit, not abuse.

In another oddly touching moment, the feverish Stanley awakens to the sound of a chorus singing “Onward Christian Soldiers” in perfect five-part harmony. He thinks he’s hallucinating until he goes to the window and sees Livingstone vigorously leading his flock in song. They may be singing phonetically, they may not know what the words mean, but they’re clearly carried away by the whole tuneful experience.

Most whites, Livingstone says, see Africa “only through the eyes of ignorance, which is to say the eyes of fear.”

“Stanley and Livingstone” is remarkable for rejecting the imperialism and casual racism that afflicted so many ’30s Hollywood movies set in the “Dark Continent.” Tracy nicely captures Stanley’s changing perspective.

In the film’s last act Stanley returns to civilization, where his account of meeting Livingstone is rejected. Only some late-arriving news prevents him from being branded a liar and opportunist.

As mentioned earlier, there are a few eye-rolling moments in the film. The filmmakers saw fit to invent a romance for Stanley with the daughter (Nancy Kelly) of the British consul to Zanzibar – it’s the thought of one day returning to this young woman that keeps Stanley going through many travails. Smart movie goers will do their best to overlook this sub plot.

Because for the most part, “Stanley and Livingstone” vividly brings history to life.

| Robert W. Butler

Leave a comment