“RAISED BY WOLVES” (HBO Max)

“Raised by Wolves” gets high marks for its ability to inspire navel-gazing and metaphysical thumb-sucking.

Problem is, I watched the first two seasons of this Ridley Scott-produced sci-fier without feeling anything. Not once. Nada.

Yeah, the series created by Aaron Guzikowski is teaming with interesting ideas. But I cared not one whit about any of the characters, their fates or the overall narrative.

Plus the actors are all saddled with the worst hair styles ever seen on television.

Initially the series sets up an intriguing premise.

In the future Earth has become uninhabitable in a civil war between true believers and atheists (sound familiar?). Things have gotten so bad that both sides make for a distant planet capable of supporting human life.

Several story threads unfold.

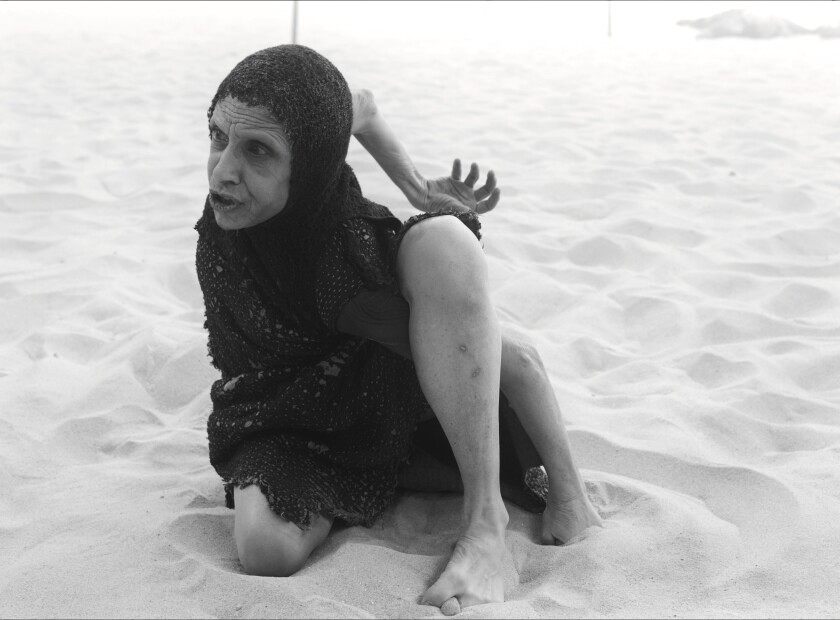

In the central one, a female android called Mother (Amanda Collin) and her assistant, Father (Abubakar Salim), travel to this new Eden. Once there they follow their programming given them by their atheist creator and start raising a family: human children who have gestated in Mother’s body.

More than a mere caregiver, Mother is a mighty weapon, a so-called Necromancer who has an arsenal of tricks worthy of Superman: heat-ray vision, the ability to fly, unmatched strength. She’ll use them to protect her offspring and to ensure the survival of rational godlessness.

Then there’’s the married couple, Marcus and Sue (Travis Fimmel, Niamh Algar) who have been carrying on a losing fight as atheist soldiers. They escape Earth by undergoing surgery so that they can replace (after assassinating) two high-ranking deists.

Thing is, the man Marcus has replaced is regarded as a prophet. It isn’t easy keeping one’s secret atheism when surrounded by believers who kowtow to your every whim; before too long Marcus undergoes a fundamental shift in thinking. Adoration goes to his head and he becomes a convert to the religion he once despised.

Parenting is a big issue here. Mother and Father must cope with the growing pains of their children and find ways to finesse the emotions that they themselves lack. Meanwhile Marcus and Sue become attached to the son of the couple they are impersonating.

In both cases we have individuals not inclined toward maternal and paternal feelings forced into positions of caring. So the series is very much about discovering one’s nurturing abilities.

And of course it’s also about faith and science, superstition and rationality, feeling and cold, hard calculation.

Yeah, all that’s in there, plus some really spectacular production design and top notch special effects.

But after the first three episodes — which promise epic things to come — “Raised by Wolves” wafts into emotional and narrative oblivion.

Plus we’re saddled with a really irritating bunch of child actors.

And, apparently, in the future humor no longer exists.

| Robert W. Butler